A Marine Reserve for Great Barrier Island?

Your chance to have a say

January 2003

Marine reserve proposal by the Department of Conservation.

This document contains all the text of the original

proposal as printed on a 16-page glossy brochure. The text in blue was

provided by us to illustrate or rebut statements. The original PDF document

can be found here

on the DoC web site (577KB+form). Recent images of the underwater world

(June 2003) have been added.

Marine Reserve status: Proposal

stage.

Closing date for objections was 30 June 2003 but has been

extended to 31 July 2003

. Click here to support/object. |

A legacy for our children

The seas around Great Barrier Island are some of the most pristine

in the Hauraki Gulf, with a remarkable variety of underwater landscapes

and marine life. However, even here, locals are reporting that fish aren't

as plentiful as they used to be. A marine reserve will ensure that at least

one part of Great Barrier's marine world is protected and replenished to

pass on to our children and grandchildren. |

Unfortunately, this area is no longer

able to replenish itself since it is degrading rapidly. Yet this was not

caused by fishing. It makes no longer sense to have a marine reserve here

because the main problem of our coastal seas, which is also manifest here,

is the devastating influence of land-based pollution. What is needed are

measures to increase the fish stocks throughout the Hauraki Gulf, and around

Great Barrier.

A decade of discussions

Over a decade ago , the Department of Conservation began talks with

tangata whenua and local residents about the need to protect Great Barrier

Island's coastal waters. Keen to establish a marine reserve somewhere around

this island, DOC circulated a public discussion paper and questionnaire

in February 1991. Over 250 people, mainly islanders, sent in their comments. |

This is a marine reserve proposal with

history. As part of the consultation process during the lead up to

the 1994 marine reserve application, a steering committee was formed at

a public meeting held at the Claris Sports Club. This committee was chaired

by John Graham and was made up of a cross section of the community, including

representatives from the South, Central and North Barrier communities,

professional and recreational fishermen, non-fishermen, at least one DoC

worker. This group eventually recommended that there was local support

for a small marine reserve as shown with the red solid lines on the map,

corresponding to the 1991 proposal. There was no support for any reserve

larger than that.

This early feedback expressed both concern over the decline in the island's

fisheries, and strong support for a fully protected marine reserve on the

island. The north-east coast was the favoured location for 75% of the people

who wrote in. Most respondents (65%) claimed that a marine reserve would

not cause problems for their current activities in the area. However, three

percent were totally opposed to any marine reserve. Restrictions on fishing

were the key concern.

Time and again, DOC quotes strong support,

whereas this was not so. For instance, at the Great Barrier Community Board

meeting of 31 May 2003 the proposal was voted down almost unanimously but

this was reported by DOC as: the vote at the meeting that was held on

GBI at the weekend was for the proposal as it currently stands. Indeed

the vote was about the current proposal. It is sad that we can no longer

trust our Government which is employing war techniques of propaganda, disinformation

and division.

Note the precise wording in the questionnaire:

Do

you support the principle of a marine reserve somewhere on the north-east

coast of Great Barrier Island? Yes/No. What are people supposed to

answer when they are against the present proposal but not against a small

reserve somewhere else? The first and foremost question should have been:

Do

you support this proposal? Yes/No.

New discoveries

Earlier discussions about possible boundaries for a marine reserve

centred on an area including the Whangapoua Estuary and beach, the coastline

immediately north and south of Whangapoua and the seas out to and surrounding

Rakitu Island.

In the years since, DOC has been carrying out further marine studies

in an area extending from Needles Point in the north to Korotiti Bay in

the south, and a large area offshore. |

Since the earlier marine reserve proposals were discussed, our knowledge

about marine environments and what is needed to best protect them has expanded.

Scientists now think that larger marine reserves may be more effective

because a larger range of habitats are protected and the effect of fishing

at the reserve edges is reduced.

Having had overwhelming adverse reaction

from the public, fishing industry, tangata whenua and community, DOC could

not come back with the same proposal. But it is true that larger marine

reserves are more effective at protecting more species and habitats. However,

marine reserves do not protect against land-based pollution and poisonous

plankton blooms. The entire proposed area has been devastated by this.

In 1993 the whole kelp forest disappeared, as did most sponges and other

sessile filterfeeders and schooling fish. Recently in 2002 this happened

again, but more devastating for sponges than for kelp. Many fish species

also disappeared. Read Seafriends' study of this phenomenon www.seafriends.org.nz/enviro/habitat/survey93.htm.

The most exciting discoveries were made in 2002, when a team of scientists

and locals sent a remotely operated camera down to 100 metre depths north

east of Rakitu. This area, shown as only slightly raised seafloor on the

marine charts, revealed a remarkable undersea world - deep water reefs

hosting coloured sponges, black coral colonies, jewel anemones - and kingfish.

DOC produced a movie from which the image on

the right was taken. The best scenes of the deep water survey by remotely

controlled camera were shown in this movie. Yet these could not hide the

overwhelming amount of mud covering the sea bottom, smothering organisms.

The organisms showed known signs of stress such as the absence of juveniles.

The large organisms in this movie have a story to tell, about how good

conditions once were but no longer are. This whole area will deteriorate

further with time, even when completely protected.

On this image one can see a dead black

coral tree in the background, covered by hardy purple jewel anemones. The

base of this tree shows that it was once a large one. |

Black coral colonies, sponges and a wealth of invertebrate

Black coral colonies, sponges and a wealth of invertebrate

life on a deep reef north of Rakitu. |

Why a marine reserve?

Marine reserves are the 'national parks' of the sea, where underwater

features and marine life enjoy complete protection. Their purpose is to

protect representative, unique or special marine habitats for scientific

study and enjoyment. |

One cannot compare marine reserves with

national parks. Our national parks are tracts of land which cannot be lived

on or harvested because they are unproductive. On the other hand, the sea

is entirely productive everywhere and can be accessed with ease. The national

parks are not threatened by muddy sediment but the sea is.

Because much of our underwater environment has been altered by human activities

we need to protect bits that represent samples of what was originally there.

Within a reserve, marine life is left to recover and flourish in its natural

state - for its own sake and for future generations. As with national parks,

people are encouraged to visit, marvel at and learn from marine reserves.

Not true. The underwater environment

is the least altered environment of all. Its kelp forests have not been

burnt for agriculture; nobody is living there; the seabottom has not been

paved with roads; there are no invasive species like cats, rats, stoats,

goats, deer, rabbits, possums. By far most of the marine life will not

improve inside a marine reserve but some fished species will to some extent.

Most Great Barrier Island locals know that the island's seas aren't as

bountiful now as they were in 'the old days'. A marine reserve will help

restore the balance and protect the marine taonga of part of Great Barrier's

coast for the benefit of present and future generations.

Speculation. Locals have worked hard

to protect their coasts with better means than marine reserves. In 1992

they achieved a 1 mile commercial set net ban right around the Great

Barrier and the Mokohinau Islands, with spectacular results. Where was

DoC when they needed them? A marine reserve will do nothing to the areas

outside and it will not address the causes of our problems.

Imagine how our fisheries could look if the option4

Principle #3 of a Planning Right was enforced. It would empower the public

to leave fish in the water, secure in the knowledge that those fish would

not simply be reallocated to the fishing industry driven by insatiable

export markets.

|

Why is the NE coast of Great

Barrier Island not what it could have been?

The green girdle of islands located

outside the coast of the mainland stretches from White Island to the Poor

Knights, including Great Barrier Island. Visit White Island or the Poor

Knights, and one experiences clear water supporting a profusion of biodiversity

under water. Obviously, the distance away from our polluting shores plays

an important factor. But why is Great Barrier not like the other, much

smaller islands?

Firstly, it encloses the Hauraki

Gulf which fills with run-off from the mainland including that from the

heavily polluted Waihou river. This runoff fertilises the plant plankton,

resulting in dense plankton blooms and a severe reduction in underwater

visibility. The over enriched waters of the Gulf have only two ways to

escape: on the south through the Colville Channel and then along the Coromandel

coast towards the Mercuries, and on the north through the Craddock Channel,

around the Needles to the east coast of the Barrier. Secondly, the Barrier

still has much barren eroding soils, a legacy from Kauri logging and poor

land management. It should be no surprise then that the proposed area suffers

from serious degradation. But what evidence exists?

The Auckland University Field trip

to Rakitu in the Christmas holidays of 1980/81 experienced such dark brown

plankton blooms (visibility 0.5-1m) that underwater surveys were not possible.

[Tane Vol 28, 1982. Little Barrier Island, Rakitu Island]

First in 1992 and again in 1993

the entire kelp forest (80-100%) deeper than 12m disappeared from the entire

area, and with it sponges, bryozoa, seasquirts and more. This also happened

in an arch around the outer Hauraki Gulf from Leigh to the Hen and Chicks.

Pelagic fish species also considerably reduced in numbers. [www.seafriends.org.nz/enviro/habitat/survey93.htm,

Floor Anthoni, 1993]

Between October and December 2002

another major kill of vertebrate species (fish) and invertebrates happened,

resulting in the almost complete loss (95-100%) of sponges and other filterfeeders

and to a lesser extent grazers such as urchins and snails. [to be published,

Floor Anthoni]

It is sad that scientists and DoC

remain uninformed about the seriousness of the situation, even though it

is there for all to see. Why have no surveys been done since 1990? The

two most devastating events happening since, have not been noticed! Obviously,

a marine reserve will not 'revert this environment to what it once was',

as repeatedly claimed by DoC and others. IT WILL NOT WORK!

Dr Floor Anthoni, June 2003 |

f036801: The kelp forest is open, letting

sunlight through to the rocky bottom. Barren patches show where large sponges

once stood. There is little kelp recruitment. The older kelp is mainly

of one age group, an indication of stress.

f036801: The kelp forest is open, letting

sunlight through to the rocky bottom. Barren patches show where large sponges

once stood. There is little kelp recruitment. The older kelp is mainly

of one age group, an indication of stress. |

f036804: A little deeper, particularly

where shelter is found, the kelp forest opens up completely, while all

the rock is covered in sticky dust. There's nobody home. The kelp forest

does not recover. (Depth 15m)

f036804: A little deeper, particularly

where shelter is found, the kelp forest opens up completely, while all

the rock is covered in sticky dust. There's nobody home. The kelp forest

does not recover. (Depth 15m) |

f036813: This vertical wall was once

covered in lush rock dwelling colonies of animals like colourful sponges,

anemones, bryozoa and hydrozoa.

f036813: This vertical wall was once

covered in lush rock dwelling colonies of animals like colourful sponges,

anemones, bryozoa and hydrozoa. |

f036814: This is a closeup of the wall

on left. Successive ecological disasters have cleared the rock, allowing

a small seaweed to colonise it.

f036814: This is a closeup of the wall

on left. Successive ecological disasters have cleared the rock, allowing

a small seaweed to colonise it. |

f036827: Remnants can be found of what

once lived on the vertical wall, but everything is covered in a sticky

mud.

f036827: Remnants can be found of what

once lived on the vertical wall, but everything is covered in a sticky

mud. |

f036819: On a ledge a number of surviving

sponges attempts to recover from near-death, but all are covered

in sticky dust.

f036819: On a ledge a number of surviving

sponges attempts to recover from near-death, but all are covered

in sticky dust. |

f036734: Behind a rocky outcrop the

cleansing action from waves can be seen. In the top right, the sessile

organisms are all clean, as is the large grey sponge. But lower down, three

grey sponges are dying because of being suffocated by sticky dust. Most

organisms occur in an advanced state of stress.

f036734: Behind a rocky outcrop the

cleansing action from waves can be seen. In the top right, the sessile

organisms are all clean, as is the large grey sponge. But lower down, three

grey sponges are dying because of being suffocated by sticky dust. Most

organisms occur in an advanced state of stress. |

f036735: another image showing how

orange stick bryozoa are just able to survive high up the rock in the current

produced by waves. But lower down organisms are dying as they have been

choked by sticky dust. Over time this rock will be as barren as the others.

f036735: another image showing how

orange stick bryozoa are just able to survive high up the rock in the current

produced by waves. But lower down organisms are dying as they have been

choked by sticky dust. Over time this rock will be as barren as the others. |

A network of marine protected areas

The

Government committed, in the New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy

(2000), to protect 10% of New Zealand's marine environment to

help conserve marine biodiversity. A network of marine protected

areas, which together protect a range of unique and diverse

habitats and ecosystems, will contribute to this target. it

may also enable marine species to move between protected areas

- a series of safe havens within movement range of adults or

juveniles. The

Government committed, in the New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy

(2000), to protect 10% of New Zealand's marine environment to

help conserve marine biodiversity. A network of marine protected

areas, which together protect a range of unique and diverse

habitats and ecosystems, will contribute to this target. it

may also enable marine species to move between protected areas

- a series of safe havens within movement range of adults or

juveniles.

The Government's policy is flawed. Marine

reserves do very little for marine biodiversity. For the non-fished species

they have no benefit, neither for the fished migratory species as they

move in and out of reserves. Only for fished resident species will they

be of benefit but these can be protected in other ways. The network idea

lives only in the minds of protagonists and has no ecological foundation

or scientific proof. Marine species moving between protected areas will

be caught just like those who live there permanently. There exists no scientific

proof that marine reserves are of benefit by their contribution of juveniles.

|

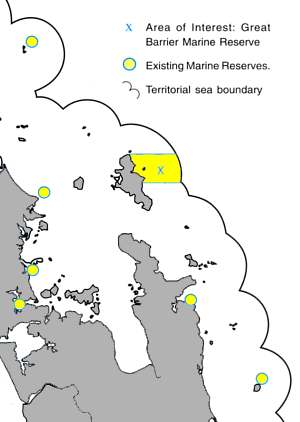

So far just 0.1% of the coast around mainland New Zealand is protected

within 15 marine reserves. There are three small marine reserves in the

Auckland region: Cape Rodney to Okakari Point (near Leigh), Long Bay to

Okura and Motu Manawa (Pollen Island) in the Waitemata Harbour. Another

- Te Matuku Bay on Waiheke Island - is awaiting approval from the Minister

of Fisheries.

Further north is the larger Poor Knights Islands marine reserve, and

to the south Te Whanganui-a-Hei (Cathedral Cove) on the Coromandel Peninsula,

and Mayor Island (Tuhua) marine reserves. It's the beginning of a network

that would be greatly enhanced by a marine reserve on Great Barrier's north-east

coast.

What are the benefits?

A marine reserve would help us to retain, in a natural and healthy

state, the great variety of plants and animals that live in the diverse

marine habitats found on the north-east coast of Great Barrier Island.

False. The marine reserve does not protect

against degradation, which is a major problem in the proposed area.

|

Marine reserves:

-

Help safeguard against environmental degradation and provide a benchmark

against which to measure human impacts in other areas. False.

They do not protect against degradation, as shown by over 2/3 of

our existing coastal marine reserves including Goat Island. Yes, they can

be used as a benchmark but it would be much better if scientists started

studying degradation, for which there exist no benchmarks: it happens everywhere.

-

Help rebuild depleted stocks of snapper, crayfish and other species, restore

kelp forests and the health of marine ecosystems. There

are better ways to do this, like fisheries regulation. The health of the

marine ecosystem is in serious decline.

-

Increase the range of fish types, as rare and more vulnerable species flourish

in the marine reserve. Rare species belong to areas

where they breed. They will continue to be rare, with or without a marine

reserve.

-

Protect the many marine processes and species we don't yet know about.

False.

These are just as much affected by degradation as others.

-

Act as a breeding area and reservoir for depleted marine species and provide

a source of larvae to boost populations inside and outside the marine reserve.

A

nice idea, but without scientific proof. Name some of the species that

will benefit. Mature snapper move out of this area into the warm Hauraki

Gulf to spawn.

-

Protect large, old experienced animals which may have important genetic

and social values not protected under fisheries rules. This

is indeed what a reserve does well, but there are other ways for achieving

this - a closed area for trawling and maximum size restrictions for instance.

But its value should not be overstated, since even at the Poor Knights

such large, old animals have not appeared.

-

Allow fish and marine life to be observed in their natural habitat, natural

sizes and numbers and exhibiting natural behaviour. There

is no objection against marine reserves in hotspots, attracting both fish

and divers. Point out on the map where such a hotspot is.

-

Provide a window on a beautiful and fascinating underwater world. Marine

reserves are ideal places for scientific study, education, snorkelling

and diving, underwater photography, swimming, exploring rock pools and

eco-tourism. Only when they do not degrade, have

clear water and easy access, will marine reserves be used by divers, underwater

photographers, eco-tourism and for education. It must be remembered that

the

best dive spots in Leigh are outside the marine reserve in an unprotected

sea.

Uses of the north-east coast

People undertake a range of activities on the north-east coast. Responses

to the 1991 questionnaire showed the most popular pastimes were swimming,

sightseeing, surfing, sunbathing and beach walking. Next were boating (including

sailing, windsurfing and water skiing) and recreational fishing. Other

activities were diving and snorkelling, education, scientific study, traditional

and commercial fishing and tramping. |

How would a marine reserve affect you?

The only activities that would be affected by a marine reserve in the

area are fishing, shellfish gathering and removal of shells. Taking any

marine life, including fishing and gathering shellfish, rocks or seaweed,

is not allowed in a marine reserve. However, fish caught outside a marine

reserve can be carried through the reserve. |

The problem of the Marine Reserves Act

is that it provides only one tool, permanent and total closure to extraction.

It is the wrong tool for this area where sustenance fishing is of major

importance. Not a word is mentioned about this in the proposal. A marine

reserve under the Fisheries Act however, would allow many degrees of flexibility

to produce the right solution for this area.

A marine reserve on the north-east coast may have economic and social implications

for commercial and recreational fishers in the area. However, fishing is

likely to improve in the areas near the reserve and, in the long term may

benefit stocks further afield. Visitors can take boats into marine reserves

and anchor but are encouraged to minimise disturbance to the sea floor.

The spill-over effect of a large marine

reserve like this is but a very small fraction (5%) of the lost fishery.

Although at the moment people have the right of 'free and innocent passage',

if fish is found on board, the onus of proof that the fish was caught outside,

will be on the fisherman and not on DOC (Marine Reserves Bill now before

parliament). In the same bill one can be fined $5000 for uprooting a kelp

plant. A marine reserve managed by DOC is just a nightmare.

A marine reserve can boost local tourism and service industries as it becomes

established. For example, the large number of visitors to the marine reserve

at Leigh has substantially benefited the local economy.

The benefit to Leigh's economy is a myth

well spread. The total benefit amounted to no more than an income for four

families, which evaporated when DOC decided to ban feeding the friendly

fishes. Here at the Barrier, one must not expect people to visit the proposed

marine reserve like the one at Leigh which is only an hour's driving from

Auckland.

Educational and recreational activities are encouraged in marine reserves,

as well as scientific research and monitoring.

Tangata Whenua

Tangata whenua have a long history of using Great Barrier's diverse

coastal resources. They continue to be kaitiaki and exercise manawhenua

over their interests in the north-east coastal area. Resident tangata whenua

are Ngati Rehua hapu and Ngati Wai iwi. Ngati Maru also have an interest

in the north-east coast and marine area. |

Many tangata whenua wish to act as kaitiaki for the estuary, within

an overall marine reserve on the north-east coast. Many tangata whenua

also support continued but limited harvesting of shellfish from Whangapoua

Estuary. This is not allowed in a marine reserve but tangata whenua needs

could be accommodated by excluding part of the estuary from the reserve

boundary.

It is here in the glossy sales brochure

that we would expect to find reference to the suite of customary maori

management tools that exist as a result of the 1992 Treaty of Waitangi

Fisheries Settlement Act and the 1996 Fisheries Act. Why do DoC continue

to pretend that these statutes are irrelevant?

Who manages marine reserves?

The Department of Conservation looks after and administers marine reserves

but relies on the support and involvement of the local community. Marine

reserve regulations are enforced by DoC, sometimes with the help of people

appointed as honorary rangers. Local people are well placed to be guardians

of a marine reserve, to watch over it and discourage potential offenders. |

Despite overwhelming scientific evidence

that local management and co-management are most desirable, DOC has explicitly

written the new marine reserves bill to exclude this. Locals must insist

on gaining control and management over any marine reserve, including control

over its entire budget. Obviously, DoC and the Marine Reserves Act are

not the right agents for this.

Local residents should be aware that policing

of this reserve is possible only by them. The vast area from 2 to 12 nautical

miles out in sea is probably unpoliceable and will be poached regularly

unless full co-operation from all fishermen is obtained.

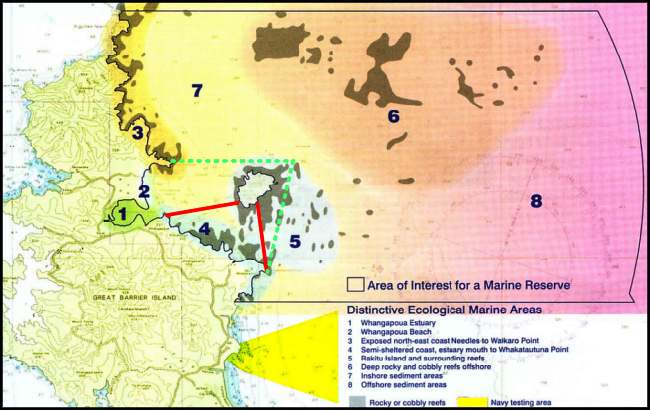

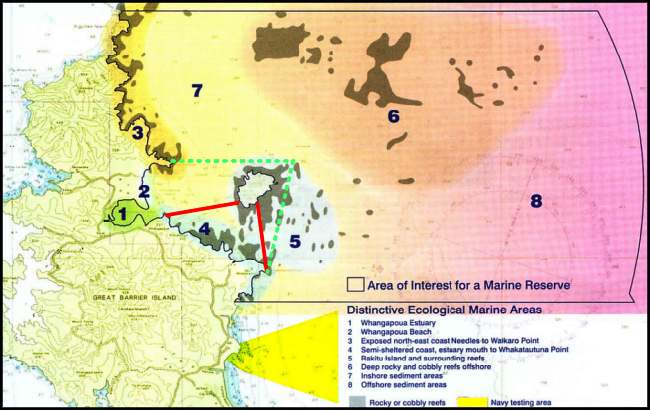

Area of interest for a marine reserve

The Department of Conservation would like to protect the full range

of coastal and marine habitats on Great Barrier Island's north-east coast.

This would provide a significant area for scientific research, and ensure

the survival of an outstanding legacy to pass on to future generations. |

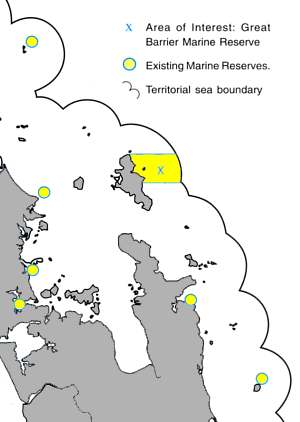

The area under investigation for a marine reserve is shown here. It

extends from Korotiti Bay to Needles Point in the far north, and from mean

high water springs out 12 nautical miles to the limits of the territorial

sea. The area includes a wide range of marine habitats, many of which are

not represented in marine reserves elsewhere. These include the estuarine

and beach areas of Whangapoua, exposed north-east coastline, semi-sheltered

coast, Rakitu Island and its surrounding reefs, deep rocky reefs offshore,

and inshore and offshore sediment areas.

Click on the map for a page-sized

version.

Only faintly visible at the bottom of

the map (but here marked in yellow) is the navy testing area where anchoring

and fishing are prohibited. This de-facto marine reserve has not been included

in the proposal, even though it would have been a good starting point.

There has not been any research conducted to ascertain whether or not the

closed area has been beneficial to the environment.

Please note the 1994 proposal boundary (marked

with a dashed line)

and the smaller boundary recommended by the Steering Committee in 1991

(marked with a solid line),

which had the support of the locals.

Does size matter?

The 'best' size for a marine reserve depends on what you are trying

to protect. For some species a very small marine reserve may be enough

to protect a local population. For species that travel or migrate a very

large marine reserve may be required to be effective. Some very mobile

species may only take up temporary residence within a reserve. Research

is continuing into effective sizes for marine reserves. |

Even more important than size is the

right choice of boundary. Marine reserve boundaries must follow ecological

boundaries that are 'meaningful' to fish. A circle around an island such

as the Poor Knights, is such an ideal boundary. The boundaries in this

proposal are convenient to humans but insignificant to fish (straight lines,

territorial sea, promontories, etc.).

Whatever the size we know that fishing for snapper and crayfish just outside

marine reserve boundaries affects numbers in the reserve. Fishing causes

these species to be generally less abundant closer to the edges of reserves

compared to the middle. Recent research at Leigh shows reduced snapper

and crayfish numbers within two kilometres from the end of the five kilometre

long reserve. A bigger reserve minimises this effect. The illustration

below shows the 'edge effect' close to the reserve boundary.

Larger marine reserves enable a wider range of habitats to be protected.

So far marine reserves in the Auckland region are relatively small. A large

marine reserve at Great Barrier would protect a wide range of habitats,

suffer minimal effects from fishing at the edges of the reserve, and would

add significantly to the network of marine protected areas in the region.

Government policy is to protect 10% of New Zealand's marine environment

(the Territorial Sea to 12 nautical miles offshore) by 2010. To date we

have protected about 4% of our territorial sea, but just 0.1% around mainland

New Zealand [1]. so we have some way to go to meet this goal.

Government's policies are flawed. The

10% is based on a comparison of the sea with our national parks, which

is invalid. Scientists have not woken up to the seriousness of environmental

degradation in the sea.

[1] The 735,000 hectare Kermadec Islands marine reserve

is much larger than any other marine reserve around mainland New Zealand

and makes up about 3.9% of our territorial sea.

What's special about the north-east coast?

Along much of Great Barrier's north-east coastline, natural habitats

extend from the hilltops to the coast and offshore. This is uncommon in

northern New Zealand due to the extent of coastal development. Because

most of the land next to the proposed marine reserve is already public

conservation land we have a chance to protect an unbroken sequence of natural

habitats - land, estuary and sea - and manage them together. |

The link between land and sea is much

overestimated but the link between salt and fresh water is real. It is

important to remember that the sea is an entirely different environment

and that it needs to be managed in a different way. DOC has shown to be

the wrong managers for the sea but they are excellent for the land.

The north-east coast is characterised by exposed rocky shores but has a

wide range of coastal features: a sheltered enclosed estuary, an open surf

beach, sheltered sandy beaches, boulder beaches and more sheltered rocky

shores. Offshore there are sandy and muddy sediments, gravel beds, reefs

and deep rocky ground. Each of these features supports a collection of

marine plants and animals adapted to the local conditions.

Warm waters from the East Auckland Current bring a subtropical influence

to the marine life found there and increase its biological diversity. These

waters are often remarkably clear which, with the diverse seascapes and

rich marine life, makes for spectacular underwater viewing.

The area is one of the last strongholds of the giant packhorse crayfish

which migrate to shallow waters around north-east Great Barrier Island

each season.

There are better ways to protect packhorse

crayfish. Besides, they have not been seen for many years. The degraded

environment is not enticing them back.

The little modified Whangapoua Estuary is home to about one third of our

remaining endangered brown teal, New Zealand's unique little duck. Sand

flats and spits around the estuary are also important feeding and roosting

areas for a significant population of the threatened New Zealand dotterel.

Do fishermen threaten the brown teal

or dotterel?

Surveys undertaken within the proposed marine reserve show a wide variety

of habitat types, including remarkable deep water reef areas with black

coral, sponges and a wealth of invertebrate life.

Needles Point and Aiguilles Island

This exposed area at the northern end of the proposed reserve is characterised

by steep dropoffs and spectacular underwater scenery. Here, hydroids and

seasquirts feature at depths of 15-20 metres and schools of kingfish and

other pelagic fish are common. |

Rakitu island

Rakitu, a small island six kilometres off Whangapoua beach, has excellent

scuba diving. Its rocky shores plunge to depths of over 30 metres where

colourful sponges and other encrusting animals cover the rocks. Underwater

archways and caves are dotted with light-shunning hydroids or sea fans

and beautiful jewel anemones. Plankton-feeding demoiselles and blue maomao

are often present. In the archways low light levels allow marine life normally

found in much deeper water to live at depths accessible to snorkellers. |

Dragon Island, Harataonga Bay

Protected from wind and waves by Rakitu, Dragon Island is only a short

snorkel from Harataonga. The eastern end of the island hosts a variety

of deep gullies and huge boulders provide sheltered nooks and crannies

for an array of reef fish. orange and green wrasse and sandagers wrasse

give a subtropical flavour to the diverse fish fauna which include black

angelfish, demoiselle, porae, blue moki, red pigfish, john dory and abundant

red moki. |

Rainbow Reef

Named after a rainbow wrasse seen here, as well as the multi-coloured

sponges and other life on the seabed, this offshore reef sits between the

Harataonga coast and Rakitu Island. At 25 metres, it's an intermediate

habitat between the deeper sponge garden and shallower Ecklonia kelp forest.

Rock outcrops emerge from a gravel floor, which has a rich flora of small

red seaweeds. The rocky reef hosts Ecklonia, mixed with sponges and hydroids,

and harbours large fish such as porae and snapper. Multitudes of small

fishes hover over the reef feeding on plankton drifting by. |

A mixture of sponges and kelp

A mixture of sponges and kelp

covers the low rocks at Rainbow

Reef. |

Colourful sponges feature in deep

Colourful sponges feature in deep

diving depths at Rakitu |

The photos shown here, taken by

Dr Roger Grace, appeared in the colourful 16-page brochure.

Although rendered rather dark, they

still reveal the degraded nature of the rocky shore environment. The depicted

orange finger sponges (Raspailia topsenti) are very hardy to degradation

by mud. It is remarkable that other types of sponge are absent from these

images. The kelp plants are all the same age since they were destroyed

in 1993. It is an unhealthy and unnatural forest now. The demoiselles in

the photo are all juvenile. In 1991 and in 2002 the majority of demoiselles

died in this area. In 2002 nearly all encrusting sponges, bryozoa and hydroids

died, as did many fish. |

In this photo also the influence

of mud can be seen. The pink coloured rocks extend above the sea bottom.

They are angular in shape meaning that they are not moved very often, unlike

rolling stones.

All plants in the image are short-lived

and attached to the clean parts of the protruding stones. This is very

much the look of a degraded environment where grazers such as urchins,

chitons and top shells have disappeared recently. |

Red seaweeds on the gravel bottom.

|

Deep water habitats

Deep rocky reefs occur to the south-east, north and north-east of Rakitu

Island, in depths of about 110 metres. surveyed by DOC in 2002 using a

special underwater camera, this rocky ground supports a rich variety of

sponges, black coral and other invertebrates, and is suitable habitat for

hapuku. Muddy sediments of the continental shelf to about 150 metres depth

extend to the 12-mile limit of the territorial sea. Deeper continental

shelf habitats like these, with their special seep water animals, are not

represented in other marine reserves. |

Ask for the video to see how much this

environment is covered in mud.

Whangapoua Estuary

Whangapoua Estuary is considered nationally important due to its large

size and undisturbed nature. Conservation land surrounds the estuary, which

provides habitat for an array of birds, shellfish and fish, as well as

the smaller bacteria and fungi on which the food chain depends. |

Conservation land does not surround

the estuary, but there is some near it. The bacteria and 'fungi' on which

the food chain depends are found in every drop of sea water and every square

millimetre of sea bottom.

The estuary 'feeds' the surrounding coastal marine communities with nutrients

supplied from the mangrove forest, seagrass and wetland areas. Snails,

crabs, worms and shellfish feed on micro organisms in the estuary, which

are then preyed on with each rising tide by snapper, yellow-eyed mullet,

flounder and rays. Along the water's edge wading birds feed on rich pickings

in the mud and sand.

Mangrove forests, seagrass and wetlands

do not supply nutrients. The mud from the land does. The number of marine

fish species depending on an estuary is very small but any species

may occasionally stray there. Estuaries like other sheltered places, help

recruitment (settling out from the planktonic stage) of some marine species.

Yellow eyed mullet has been observed to go upstream into freshwater and

wetlands to spawn.

The estuary supports significant numbers of the threatened New Zealand

dotterel and is a stronghold for one of our most endangered endemic ducks,

the brown teal. The spit is a high tide roost and the mudflats a feeding

ground for coastal birds, including the Pacific golden plover, banded dotterel,

bar-tailed godwit, variable oystercatcher and pied stilt.

Does fishing affect these?

The

expansive pipi and cockle beds in the estuary are an important shellfish

gathering area for local people and tangata whenua. From consultation

it was noted that shellfish are less abundant elsewhere on Great Barrier

and that shellfish populations at Whangapoua are under pressure from

the summer influx of visitors to the island. Many locals have said

they should be able to continue to have a sustainable but small harvest

of the main shellfish species from the estuary. This view has been

endorsed by tangata whenua as kaitiaki of the estuary. The

expansive pipi and cockle beds in the estuary are an important shellfish

gathering area for local people and tangata whenua. From consultation

it was noted that shellfish are less abundant elsewhere on Great Barrier

and that shellfish populations at Whangapoua are under pressure from

the summer influx of visitors to the island. Many locals have said

they should be able to continue to have a sustainable but small harvest

of the main shellfish species from the estuary. This view has been

endorsed by tangata whenua as kaitiaki of the estuary.

Shellfish beds thrive from a moderate

amount of exploitation. The front page of the coloured brochure shows tracks

in the sand caused by cockles on the move from crowded areas. This is a

symptom of under-harvesting. By judicious harvesting, people can enhance

the productivity of cockle beds. The problem is that the MRA does not provide

enough flexibility for allowing a limited and supervised harvest. DOC is

the wrong agent and the MRA the wrong tool for marine reserves in the 21st

century.

To address these concerns, an exclusion zone could be established within

the Whangapoua Estuary to allow an ongoing sustainable harvest of shellfish.

DOC is seeking your views on whether an area should be set aside for shellfish

gathering and in what location.

What happens next?

After further consultation with tangata whenua, fishers, interested

groups and the Great Barrier community, and consideration of feedback on

this discussion document, DOC will make a formal application to the Director

General of Conservation for a marine reserve. Members of the public then

have two months, from the time the application is notified, to make submissions. |

The Minister of Conservation will make the final decision on the application,

which also requires agreement from the Ministers of Fisheries and Transport.

Locals are very wary of DoC handling

the submission. They have been through the process twice. When will a final

rejection be respected?

Establishing a marine reserve

Pre Statutory Process

(the proposal stage)

| Define objectives |

See objectives below |

| Initial consultation with interested groups |

1991 onwards

There was support for a small reserve. |

| Site survey and investigations |

1990 onwards |

| Draft proposals formulated and public feedback incorporated |

1991 & 1994

Rejected by a vast majority |

| Community consultation. Dicsussion document circulated for comment

before preparing formal application. |

2003 |

[The table of the pre-statutory and

statutory process have been left out to save space. Click

here for details, including the new statutory process

as proposed in the Bill now before Parliament. It bears no

relevance to this particular proposal since it forms part

of every marine reserve proposal. ] |

The objectives of a marine reserve on Great Barrier

island are:

-

To establish a marine reserve conforming to provisions of Sections 3(1)

and 3(2) of the marine Reserves Act 1971.

-

To protect and maintain a large section of the diverse marine ecosystem

and biodiversity on the north-east coast of Great Barrier island, that

is ecologically continuous with already protected adjacent terrestrial

habitats.

-

To protect a wide variety of marine habitats and their marine life, including

continental shelf deep water rocky and sediment habitats not represented

in marine reserves elsewhere.

-

To provide a safe haven for several species of marine animals presently

impacted by fishing, and to allow them to recover to their natural population

and social structure.

-

To provide a marine reserve which is large enough to minimise side effects

of fishing, and to provide a large central core area of protection to allow

ecological, social and behavioural characteristics of marine communities

to function without interference.

-

To provide opportunities for scientific study, including study of the relative

merits of large versus small marine reserves.

-

To provide opportunities for public enjoyment of non-extractive high quality

marine recreational activities.

-

To form a link in the national network of marine reserves in accordance

with New Zealand's Biodiversity Strategy (He Kura Taiao) and to contribute

towards the Government's target of protecting 10% of New Zealand's marine

environment by 2010.

Do you really think the above objectives will

be met? The era for coastal marine reserves has passed. Our seas can be

saved only by saving the land and by improving fisheries regulations. Our

only option is to stop the whole marine reserves process so that lies,

myths and fallacies can be ironed out and solutions found that will work.

An A4-sized

map is also available. Visit www.seafriends.org.nz

for more information on marine conservation and reserves.

NOW - Make your submission

- click this link to have your voice heard

|

The

expansive pipi and cockle beds in the estuary are an important shellfish

gathering area for local people and tangata whenua. From consultation

it was noted that shellfish are less abundant elsewhere on Great Barrier

and that shellfish populations at Whangapoua are under pressure from

the summer influx of visitors to the island. Many locals have said

they should be able to continue to have a sustainable but small harvest

of the main shellfish species from the estuary. This view has been

endorsed by tangata whenua as kaitiaki of the estuary.

The

expansive pipi and cockle beds in the estuary are an important shellfish

gathering area for local people and tangata whenua. From consultation

it was noted that shellfish are less abundant elsewhere on Great Barrier

and that shellfish populations at Whangapoua are under pressure from

the summer influx of visitors to the island. Many locals have said

they should be able to continue to have a sustainable but small harvest

of the main shellfish species from the estuary. This view has been

endorsed by tangata whenua as kaitiaki of the estuary.

The

Government committed, in the New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy

(2000), to protect 10% of New Zealand's marine environment to

help conserve marine biodiversity. A network of marine protected

areas, which together protect a range of unique and diverse

habitats and ecosystems, will contribute to this target. it

may also enable marine species to move between protected areas

- a series of safe havens within movement range of adults or

juveniles.

The

Government committed, in the New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy

(2000), to protect 10% of New Zealand's marine environment to

help conserve marine biodiversity. A network of marine protected

areas, which together protect a range of unique and diverse

habitats and ecosystems, will contribute to this target. it

may also enable marine species to move between protected areas

- a series of safe havens within movement range of adults or

juveniles.